exhibition

02 October 2020 > 18 April 2022

senzamarginePassages in Italian Art at the Turn of the Millennium

Access to galleria 1 is free of charge from Tuesday to Thursday.

galleria 1

curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi

single ticket valid until 17 April, for all ongoing exhibitions, due to the refurbishment of 2 galleries

– for young people aged between 18 and 25 (not yet turned 25);

– for groups of 15 people or more;

– La Galleria Nazionale, Museo Ebraico di Roma ticket holders;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Accademia Costume & Moda, Accademia Fotografica, Biblioteche di Roma, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Enel (for badge holder and accompanying person), FAI Fondo Ambiente Italiano, Feltrinelli, Gruppo FS, IN/ARCH Istituto Nazionale di Architettura, Sapienza Università di Roma, LAZIOcrea, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Amici di Palazzo Strozzi, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Scuola Internazionale di Comics, Teatro Olimpico, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Teatro di Roma, Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata, Youthcard;

– upon presenting at the ticket office a Trenitalia ticket to Rome purchased between 27 November 2024 and 21 April 2025

valid for one year from the date of purchase

– minors under 18 years of age;

– myMAXXI cardholders;

– on your birthday presenting an identity document;

– upon presentation of EU Disability Card holders and or accompanying letter from hosting association/institution for: people with disabilities and accompanying person, people on the autistic spectrum and accompanying person, deaf people, people with cognitive disabilities and complex communication needs and their caregivers, people with serious illnesses and their caregivers, guests of first aid and anti-violence centres and accompanying operators, residents of therapeutic communities and accompanying operators;

– MiC employees;

– journalists who can prove their business activity;

– European Union tour guides and tour guides, licensed (ref. Circular n.20/2016 DG-Museums);

– 1 teacher for every 10 students;

– AMACI members;

– CIMAM International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art members;

– ICOM members;

– from Tuesday to Friday (excluding holidays) European Union students and university researchers in art history and architecture, public fine arts academies (AFAM registered) students and Temple University Rome Campus students;

– IED Istituto Europeo di Design professors, NABA Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti professors, RUFA Rome University of Fine Arts professors;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Collezione Peggy Guggenheim a Venezia, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Sotheby’s Preferred, MEP – Maison Européenne de la Photographie;

for groups of 12 people in the same tour; myMAXXI membership card-holders; registered journalists with valid ID

under 14 years of age

disabled people + possible accompanying person; minors under 3 years of age (ticket not required)

MAXXI’s Collection of Art and Architecture represents the founding element of the museum and defines its identity. Since October 2015, it has been on display with different arrangements of works.

Access to galleria 1 is free of charge from Tuesday to Thursday.

galleria 1

curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

From her debut in 1947 with the abstract group Forma 1, and until her death, Carla Accardi (1924-2014) was one of the most original figures of art in Italy. Her research immediately turned towards the abstract sign, condensed from the early 1950s in its most characteristic figure, a «cloud» of signs linked to each other and arranged on monochrome backgrounds. From the mid-1960s, the artist substitutes canvas with a semi-rigid transparent plastic medium, sicofoil, on which she applies intensely coloured signs which in some cases also cover the frames behind them; this gesture frees the sign in space, giving these accumulations a three-dimensional character. The investigation of the sign will accompany the artist throughout her career up to the most recent works, such as the two canvases Bianco argento [White silver] on show, on which simplified and geometric signs appear, typical of her later style.

With the series of sicofoil Rotoli [Rolls] and Tende [Tends], Accardi’s work conquers three-dimensional space and enters into a relationship with the scale of the human body, to the point of proposing, with Triplice tenda [Triple tend] (1969-71), a direct confrontation with existential, psychic and political depth, connected with the notion of habitat. Through the use of transparency and light, Accardi shows the possibility of going beyond the traditional, rigid structures of painting (the picture) and architecture (the house) and the social roles that are connected with them, including those more directly linked to a women’s condition to be liberated and reinvented (it is no coincidence that her adherence to the feminist movement dates back to the same period). These themes resurface after three decades in Casa Labirinto [Labyrinth House], exhibited for the first time at Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Valmontone in 2000, this time using a rigid Perspex support that takes the shape of a parallelepiped crossed by transparent perpendicular planes on which the artist has drawn black and grey signs on vertical bands. As always for the artist, pictorial work, architectural structure and symbolic plan tend to form a single sphere of experience. The «house» then becomes a place in which to imagine new ways of existence, under the banner of a utopian aspiration of which Accardi’s work has made itself subtle and tenacious messenger down to the very last.

Casa Labirinto, 1999-2000

enamel on Perspex, wooden base

Courtesy: Archivio Accardi Sanfilippo, Roma

Bianco argento, 2000

vinyl paint and enamel on canvas

MAXXI Collection

Bianco argento 3, 2001

vinyl paint and enamel on canvas

MAXXI Collection

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Engaged in the renewal of sculpture from the mid-1960s onwards, Luciano Fabro (1936-2007) – one of the best-known figures of Arte Povera and passionate theorist and teacher – was one of the protagonists of the international artistic scene. His research has focused on hybridisations and unusual combinations of materials, techniques, figurative suggestions and conceptual aspects of the sculptural language, in constant dialogue with the historical and cultural reality of his time.

The first of the two works on display, Enfasi (Baldacchino) [Emphasis (Canopy)], consists of a horizontal structure, made of alternating strips of copper and aluminum, on which eighteen metal rods are arranged, each bearing a face embossed as in ancient Roman clipei. Suspended at the top, like a canopy, the work has the appearance of a precious artefact, a cover with sacred and liturgical echoes intended to accompany a ritual procession or even indicate a highly significant place, that in which the spectator is located.

The second work, Italia all’asta [Italy for auction] belongs to one of the most well-known series of Fabro’s work, that of the so-called Italie, started in 1968. The cycle, translated into different materials and solutions, revolves around the iconographic theme of the Italian peninsula and composes an acute reflection on national identity, investigated in its various social, political and historical aspects. In the work, two profiles of Italy, one of them upside down, are made of iron sheet and hung on a pole resting on a wall – the north of one joined with the south of the other and vice versa, and the major islands joined to the centre. In Italian, the title plays on the ambiguity between the literal meaning of ‘asta’ as «pole», which bears an image, brought back by Fabro to the Baroque festival, and as «auction» that suggests sale at auction. The origin of Italia all’asta dates back to the mid-1980s, the moment when the process of divesting large public companies and the season of privatisation that was to culminate in the following decade began. In this case, the contemporary events of Tangentopoli add a further level of meaning to the work, which thus registers the moment of profound crisis in Italy.

Enfasi (Baldacchino), 1982

aluminum and copper structure

Private Collection

Italia all’asta, 1994

painted iron

MAXXI Art Collection

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Photographer, theorist, editor, curator and cultural animator Luigi Ghirri (1943-1992) has been a key figure in contemporary visual culture since the late 1960s. At the start of the 1970s, he began a major phase of experimentation with photography, thanks also to his early and original use of colour film. His work exhibited a conceptual component that would always remain characteristic of his practice. Ghirri’s career started with an investigation of his homeland, Emilia-Romagna, centred on the definition of a new strategy of observation: photography became a tool for the investigation of the surrounding environment, to reveal places that do not chime with the stereotypical image of Italy and to establish a new relationship with the area, revealing its deepest mysteries. This journey culminated in Viaggio in Italia [Journey in Italy, 1984], a project that brought together a new generation of Italian photographers.

The photographs presented here come from the archives of the «Lotus International» journal, with which Ghirri published his volume Paesaggio italiano [Italian Landscape] in 1989. This was one of the most important projects in the artist’s career and testifies to a major phase in his work: after his initially more conceptual projects, his interpretation of the landscape became more lyrical and allusive in the 1980s. In Paesaggio italiano, Ghirri collects a selection of photographs taken after 1970 and «mounts» them in an unedited sequence. He finds a common thread in them despite the diversity of the sources: «a leitmotif» – he writes – «that cuts across themes, spaces and objects» and unites the photographs in a kind of «sentimental geography where the routes are not precise or marked out, but obey strange entanglements of seeing, […] substituting the burden of the already lived and seen with a look that erases and forgets habit».

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

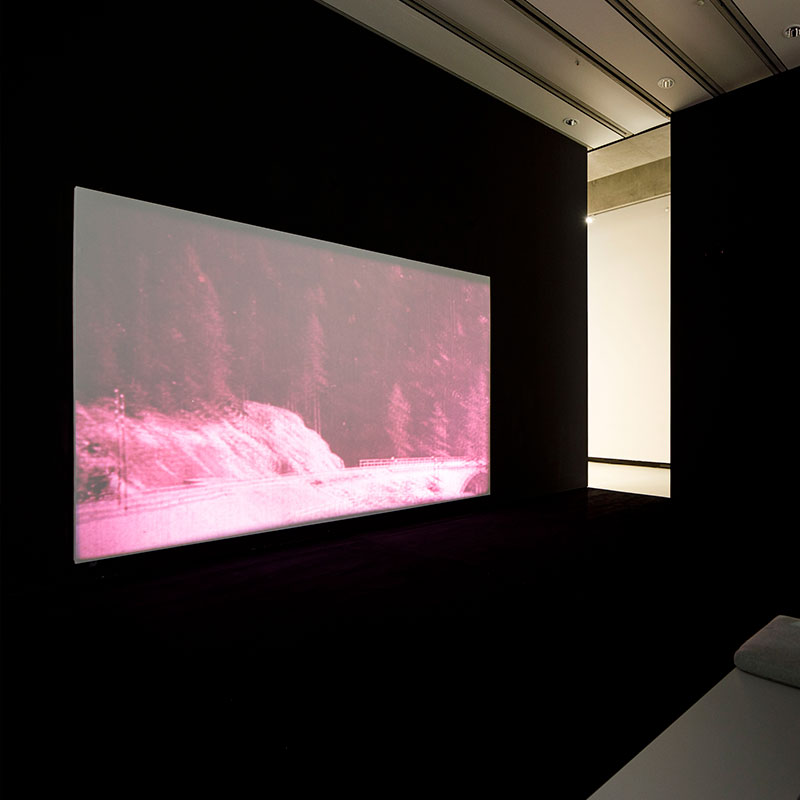

Since the early 1980s, Yervant Gianikian (1942) and Angela Ricci Lucchi (1942-2018) have been building their films on archival films, recovered and enhanced to explore the political, historical and anthropological aspects of moving images and re-discuss their traditional narrative categories. Between 1984 and 1986, the two artists created Dal Polo all’Equatore [From the Pole to the Equator] based on the archives of filmmaker and documentary maker Luca Comerio (1878-1940), which were rich in materials filmed during the period between the two world wars. They find themes such as travel, exploration, conquest, cultural and religious submission of African populations, exotic adventure, and military and colonial oppression. To produce their films, the artists use an «analytical camera» consisting of two elements: in the first, the original 35 mm film runs vertically, operated by hand given the fragility of the material; the second, a camera aligned with the first element, allows the original images to be re-photographed in transparency. The work – accompanied on show by a large drawn «scroll» and other works on paper – raises fundamental questions about the relationship between cinema and history: the function of the word and the role of real time (and slow motion) in film, the value of testimony of documentary images.

This research continues in the following years in works such as Uomini, anni, vita [Men, Years, Life] (1991) on the genocide of the Armenians of Turkey (which Gianikian’s father fled from) and in the project Archivi Italiani [Italian Archives], based on films and images of the twenty years of Fascism, with Il fiore della razza [The Flower of the Race] (1991), Prigionieri della guerra [Prisoners of War] (1995) and Lo specchio di Diana [Diana’s Mirror] (1996). After Tourisme vandale [Vandal Tourism] (2001), on colonialism hidden in fascination for the exotic, they complete Oh! Uomo [Oh! Man] (2004) which dismantles the militarist ideology of the First World War through a sort of anatomical catalog of wounded and mutilated bodies. After the death of Angela Ricci Lucchi in 2018, Yervant Gianikian realizes Il diario di Angela, Noi due cineasti [Angela’s Diary, Two Filmmakers] (2018-19), a two-part film on their long shared journey.

Dal Polo all’Equatore, 1984-1986

16mm film transferred in 35mm (101″) and digitally (96″), sound, 4:3

MAXXI Collection

Dal Polo all’Equatore, 1985

pencils on paper

MAXXI Collection

Dal Polo all’Equatore, 1982-1985

4 elements, graphite on paper

MAXXI Collection

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Starting from the mid-1960s, the research of Paolo Icaro (1936) integrates a reflection into sculpture both on its spatial characteristics and on its temporal and mental aspects. For Icaro, space is to be experienced with the body and sought in the becoming of time, in a dimension in which project and chance, intimacy and irony, come together in a continuous making and undoing of form and thought. After having participated in the first Arte Povera exhibitions and the main international shows of Process Art, starting in the 1970s he follows an independent path, outside of groups and trends, which takes him to different places – from Turin to Rome, from New York to Genoa – following the thread of his personal exploration of materials and the limits of sculptural language, up to the complete deconstruction of form.

In 1981, Icaro returns to Italy after a long stay in the United States; from this moment an interest in the «classic making» of sculpture again becomes central in his work and plaster – a ductile and readily available material that allows him to work with an elementary gestural expressiveness and indulge the organic growth of matter – becomes the most suitable material for his research. In Spiette [Spy holes], a work displayed for the first time in an environmental dimension, Icaro punctuates space with 36 small plaster castings in which fragments of mirror glass are embedded. Positioned at different angles, the Spiette throw back a fragmentary image of surrounding space, in which, from reflection to reflection, the mirroring points weave an invisible web of glances. From the ceiling to the walls, the radiant energy spreads to the floor, where some scattered elements indicate further paths of proliferation and expansion of matter. For Icaro, the fragment does not refer to an image or an irremediably lost completeness, but contains within itself the vital force of future completion. It is therefore continuity in power – of doing and of a cultural identity -, yearning for an ideal unity in which past and future come to coincide in the present, in that space which is «the always of time» for Icaro.

Spiette, 36, 1991

Installation in situ, 36 elements: plaster and mirror glass

MAXXI Collection

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Leaving Greece for Rome in 1956, where he lived and worked until his death, Jannis Kounellis (1936-2017) is one of the best-known figures in Arte Povera. From the second half of the 1960s onwards the vocabulary of his work consists of elementary materials (wool, coal, gold, iron, stone, lead, coffee, wood, etc.), open flames, casts of statues, furniture and clothes, plants and living animals, as in the memorable exhibition of twelve horses at L’Attico gallery in Rome in 1969. The use of non-traditional materials, as well as music or performance, allows Kounellis to go beyond the limits of sculpture, expanding it in space and time in installations conceived as visualisations of powerful flows of plastic and symbolic energy. With his eyes on both artistic and cultural tradition and the historical tragedies and utopias of the twentieth century, Kounellis’s work explored the anthropological and political dimensions of the experience of artistic creation with great intensity, following the directions of a lucid humanism and uncompromising «passion for the real».

The installation on show, Untitled, presented for the first time in Todi and then in London in 2014, is one of the last created by the artist. Enveloping the space, «tracks» made of iron beams are arranged on four walls. Large butcher knives with handles wrapped in newspaper poke out from the beams and black coats reduced to shreds, in turns, hang out at the end of the blades. In the centre of the space a single «column» raises other coat flaps. The work refers to several previous installations by Kounellis – such as the series of lit gas beaks arranged on a wall (Paris, 1969) or the slaughtered meat hanging on iron plates (Barcelona, 1989) – and stands as an extreme, pessimistic meditation on the dialectical clash between historical forces and individual destiny, between violence and collective redemption. In a note from 1982, Kounellis wrote: «I seek […] dispersed history in (emotional and formal) fragments. I am dramatically looking for unity, even if hard to grasp, albeit utopian, albeit impossible and, for that reason dramatic».

Senza titolo, 2014

iron, knives and coats

Courtesy: Estate of Jannis Kounellis and Sprovieri Gallery, London

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

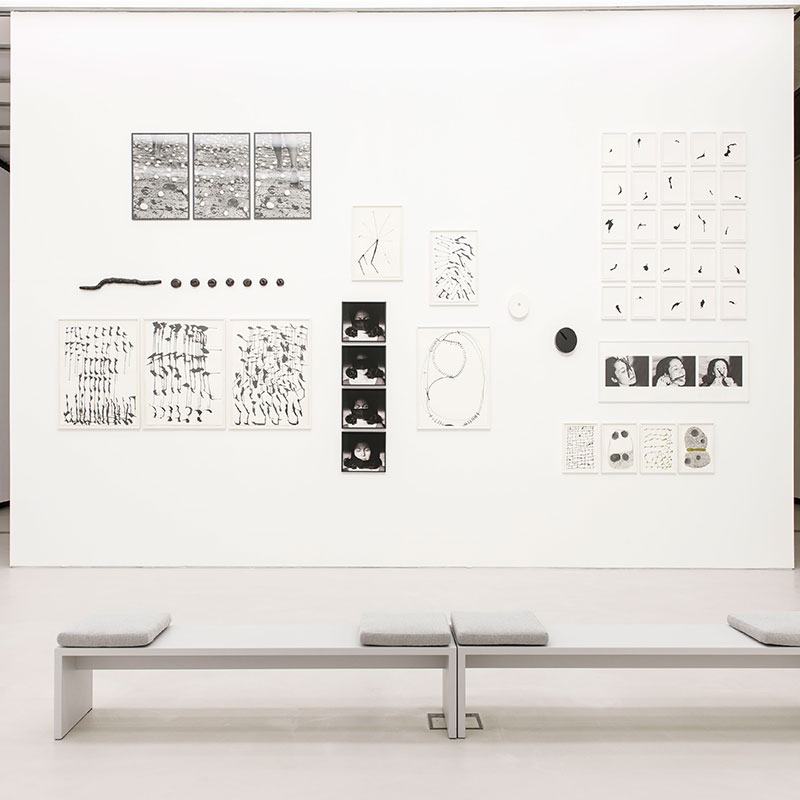

Born in Italy in 1942, Anna Maria Maiolino moved with her family in 1954 to Venezuela and then to Brazil, to Rio de Janeiro, where she studied at the School of Fine Arts in 1960. Here she meets artists such as Antonio Dias and Rubens Gerchman and comes into contact with exponents of the neo-concrete movement such as Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, approaching their conception – expressed in Ferreira Gullar’s manifesto Teoria do não-objeto – of the artistic object as a «quasi-corpus» which activates a form of sensory knowledge. This philosophy, together with her fascination for matter, has influenced the artist’s practice since the beginning in the late 1960s. Maiolino queries the interaction between spectator and work – usually with a markedly bodily appearance as can also be seen in one of her later works, 7 + 1, série Objeto Escultórico (1999) – and the interaction between different means of expression, an interaction that emerges clearly in the installation proposed here and designed specifically for this exhibition.

Attention to the body, in particular the female body, and the mixture of different languages in the same work become evident in the famous Fotopoemação series, photographs poised between poems and performances located on the border between different artistic genres. In É o que Sobra – série Fotopoemação (1974-2000), for example, which recalls the contemporary manifestations of international Body Art, Maiolino simulates the mutilation of parts of her face (tongue, nose, eyes), while the triptych Entrevidas (1981-2000) documents the artist’s walk on an egg-covered road. Here the egg, a symbol of life and fertility, a fragile and ephemeral object, symbolises the precariousness of human life and culture, threatened by the military dictatorship (1964-1985) that pushed many artists to leave Brazil. Of particular importance is also the recent return to drawing, in the guise of «anthropomorphic signs» halfway between sculpture and graphics, as seen in Sem título, série Marcas da Gota N (2010), and Sem título, série Interações (2013).

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

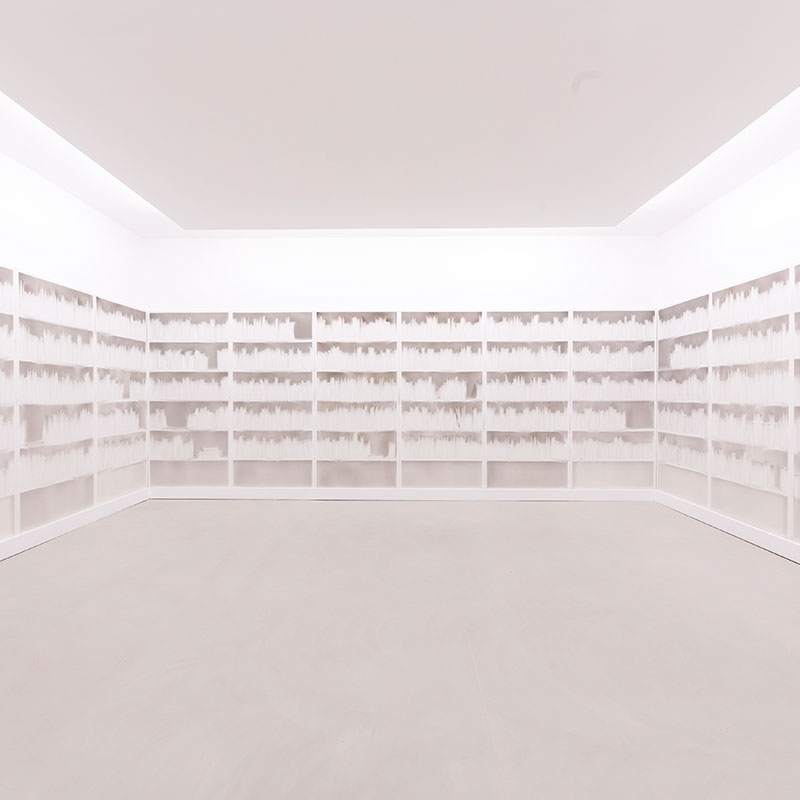

Claudio Parmiggiani (1943), one of the most internationally known Italian artists, chose to live the condition of «secluded», that is, distant from the groups and trends that dominated the second half of the twentieth century, to the point of defining himself in one of his texts a «stylite», a hermit figure. Since his debut in the mid-1960s, his work has reflected on the nature of images, their cultural roots and their emotional resonances, using a wide range of materials and media, from photography to casting, from fragment to imprint and assemblage. Recurring themes in Parmiggiani’s work are solitude, silence, memory, an attitude that reconciles the deepest spirituality and the most radical materialism. His shadow sculptures, as they have been defined, often evoke disappeared bodies and objects, always avoiding the pure intellectual game that most often accompanies the themes of absence and trace.

In his work, disappearance always has something traumatic and spectrally theatrical: it alludes to the lacerating disappearance of things and people, burned by the stake of History. Starting in 1970, the artist’s preferred material is indeed the shadow, elusive and at the same time piercing, which he projects into the environment with the method of «delocalisation», that is, using fire, soot and smoke that reveal the shape of absent objects. One of the subjects most frequently «treated» with this method is the book: a symbolic form with long-lasting cultural and sapiential value, but also a solid material entity with a rich formal history. In Parmiggiani’s invisible libraries the book becomes a figure of the human mind and memory and, therefore, of everything that in our present never ceases to disappear and to incinerate itself.

Senza titolo, 1998-2020

smoke and soot on wood panel

MAXXI Collection

foto © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Painting, photography and film have been the three ways in which Mario Schifano’s research (1934-1998) has always been expressed. Since the early 1960s, the artist has been one of the protagonists of «new figuration», close to Pop Art, and a keen observer of the simulacra of mass society, rendered in fragmentary and impersonal forms on monochrome backgrounds that seem to recall cinema or television screens. From the 1970s onwards, the television reference becomes increasingly important, especially with Paesaggi T.V. [TV Landscapes], television sequences photographed and then shown on the pictorial surface. During the following decade, Schifano’s palimpsest canvases began to be populated with images of an ever more saturated contemporaneity, filtered by modern means of communication. In the same period, dominated by the new postmodern sensibility, Schifano, having returned to using painting, created demanding works, often of considerable size, characterised by a rich chromatic matter and free, wild signs, similar to those of contemporary neo-expressionist currents.

In the paintings exhibited here – originally presented in Rome in 1990 in the Divulgare exhibition at Palazzo delle Esposizioni, and partly damaged by fire in 1992 – Schifano returns to meditate on the anesthetising power of television – at the same time fetish and personal obsession – focusing on constant exposure to an overdose of images increasingly emptied of meaning. Emblematic in this sense are the circular works Chi [Who] and Dolore [Pain], dominated by the elusive profiles of figures with fixed and highlighted eyes. On the other hand, in the large panel entitled Per Esempio [For Example], Schifano seems to weave a private inventory of images drawn from the most varied contexts, super-imposing references to the history of art (Andy Warhol, Giorgio de Chirico, Pablo Picasso), to politics (among others, the faces of Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev), along with banal images and the indefinite flashes emitted by the television screen. In the same way, in the work Segni [Signs], the artist collects a sort of sample of frames from pictorially manipulated videos.

Dolore, 1990

mixed technique

Courtesy: Collezione Jacorossi, Roma

Chi, 1990

mixed technique

Courtesy: Collezione Jacorossi, Roma

Per Esempio, 1990

print on PVC and painting interventions

Courtesy: Collezione Jacorossi, Roma

Segni, 1990

mixed technique

Courtesy: Collezione Jacorossi, Roma

Ritracciato, 1990

mixed technique

Courtesy: Collezione Jacorossi, Roma

CARLA ACCARDI | LUCIANO FABRO | YERVANT GIANIKIAN E ANGELA RICCI LUCCHI | PAOLO ICARO | JANNIS KOUNELLIS | ANNA MARIA MAIOLINO | CLAUDIO PARMIGGIANI | MARIO SCHIFANO

On the Museum’s tenth anniversary – inaugurated on May 30, 2010 – a new large display enhances the Collection’s project, displaying in the gallery dedicated to it a nucleus of works by nine masters representing the vitality and diversity of artistic research in Italy. Masters not yet present in the MAXXI Collection and who, thanks to a contribution from the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism on the occasion of this important anniversary, will become part of it.

Set in a sequence of immersive environments that enhance their revolutionary charge, strength and monumentality, as well as their relationship with space, the chosen works created by Italian masters, or active in Italy. Often considered to be on the margins of the most well-known movements, over the years these artists have been able to maintain independent and original research, such as to be considered a reference point for the artists of subsequent generations.

ON DISPLAY

Carla Accardi

Luciano Fabro

Luigi Ghirri

Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi

Paolo Icaro

Jannis Kounellis

Anna Maria Maiolino

Claudio Parmiggiani

Mario Schifano

contenuti correlati

listen to the mood guide

No margin, no borders, no boundaries. A playlist designed to accompany the journey through the various works and rooms, follow a route, stop, go back, and start again. It can be taken as a flow or as a single counterpoint to the works on display. It works both ways; it is up to you to figure out which one suits you best.

curated by Emiliano Colasanti