- special reduced price € 10

single ticket valid until 17 April, for all ongoing exhibitions, due to the refurbishment of 2 galleries

- full price € 15 at the box office - € 14 online

- reduced price € 12 at the box office - € 11 online

– for young people aged between 18 and 25 (not yet turned 25);

– for groups of 15 people or more;

– La Galleria Nazionale, Museo Ebraico di Roma ticket holders;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Accademia Costume & Moda, Accademia Fotografica, Biblioteche di Roma, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Enel (for badge holder and accompanying person), FAI Fondo Ambiente Italiano, Feltrinelli, Gruppo FS, IN/ARCH Istituto Nazionale di Architettura, Sapienza Università di Roma, LAZIOcrea, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Amici di Palazzo Strozzi, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Scuola Internazionale di Comics, Teatro Olimpico, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Teatro di Roma, Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata, Youthcard;

– upon presenting at the ticket office a Trenitalia ticket to Rome purchased between 27 November 2024 and 21 April 2025 - open € 18

valid for one year from the date of purchase

- free

– minors under 18 years of age;

– myMAXXI cardholders;

– on your birthday presenting an identity document;

– upon presentation of EU Disability Card holders and or accompanying letter from hosting association/institution for: people with disabilities and accompanying person, people on the autistic spectrum and accompanying person, deaf people, people with cognitive disabilities and complex communication needs and their caregivers, people with serious illnesses and their caregivers, guests of first aid and anti-violence centres and accompanying operators, residents of therapeutic communities and accompanying operators;

– MiC employees;

– journalists who can prove their business activity;

– European Union tour guides and tour guides, licensed (ref. Circular n.20/2016 DG-Museums);

– 1 teacher for every 10 students;

– AMACI members;

– CIMAM International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art members;

– ICOM members;

– from Tuesday to Friday (excluding holidays) European Union students and university researchers in art history and architecture, public fine arts academies (AFAM registered) students and Temple University Rome Campus students;

– IED Istituto Europeo di Design professors, NABA Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti professors, RUFA Rome University of Fine Arts professors;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Collezione Peggy Guggenheim a Venezia, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Sotheby’s Preferred, MEP – Maison Européenne de la Photographie;

Casa Balla | until 27 April 2025

- full price ticket € 18

- reduced price ticket € 15

for groups of 12 people in the same tour; myMAXXI membership card-holders; registered journalists with valid ID

- reduced price ticket € 12

under 14 years of age

- free ticket

disabled people + possible accompanying person; minors under 3 years of age (ticket not required)

Collection

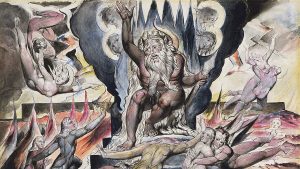

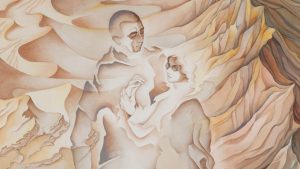

MAXXI’s Collection of Art and Architecture represents the founding element of the museum and defines its identity. Since October 2015, it has been on display with different arrangements of works.

other upcoming events

8 Apr 2025 06.00 pm

talkCulinary interpretation of the arts

8 Apr 2025 06.00 pm

books at MAXXIJoker scatenato. Il lato oscuro della comicitàby Guido Vitiello

9 Apr 2025 06.00 pm

books at MAXXIVite nell’oro e nel bluby Andrea Pomella

10 Apr 2025 06.00 pm

books at MAXXILa mummia di Leninby Ezio Mauro

12 Apr 2025 05.00 pm

MAXXI with the familyDi Spazio in SpazioDivento Spazio

13 Apr 2025 05.00 pm

MAXXI with the familyDi Spazio in SpazioDivento Spazio

«The MAXXI has never kneeled down in front of all difficulties but this time we kneel down for our brothers and sisters, so we can stand up all together, forever». Hou Hanru, Direttore Artistico MAXXI

MAXXI supports culture in favour of inclusion and equality, especially in such a difficult historical moment for all like the one we’re living.

The MAXXI’s Instagram page feed becomes the medium for raising awareness and consciousness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

And it does so through art, through the history of its exhibitions. We have chosen words and images of artists, who place hope and focus on the reality of a global problem that can no longer be ignored.

Follow #MAXXIforBlackLivesMatter on Instagram

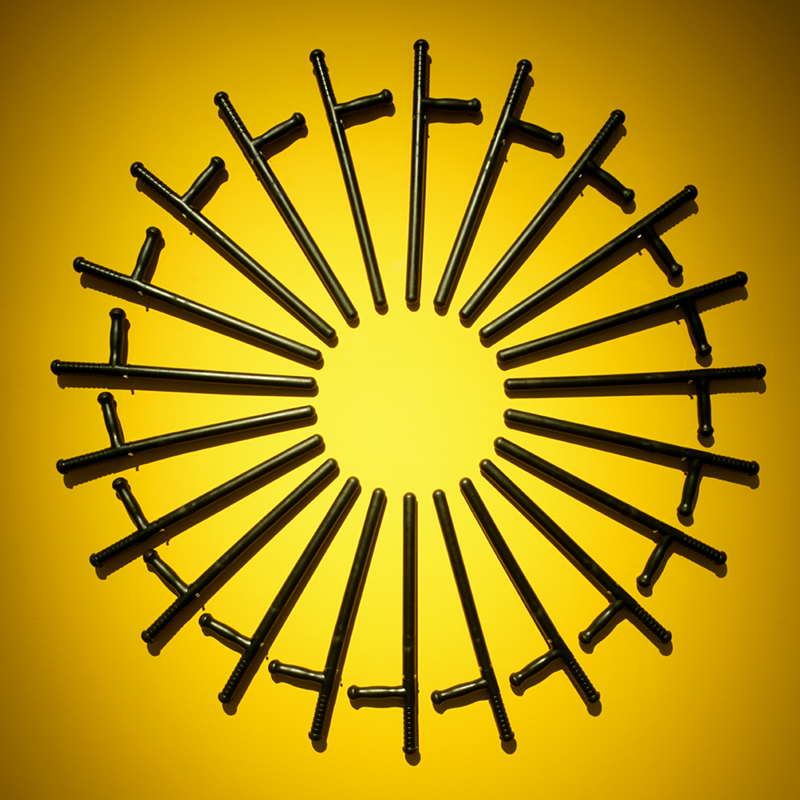

KENDELL GEERS

T. W. Batons (Circle), 1994

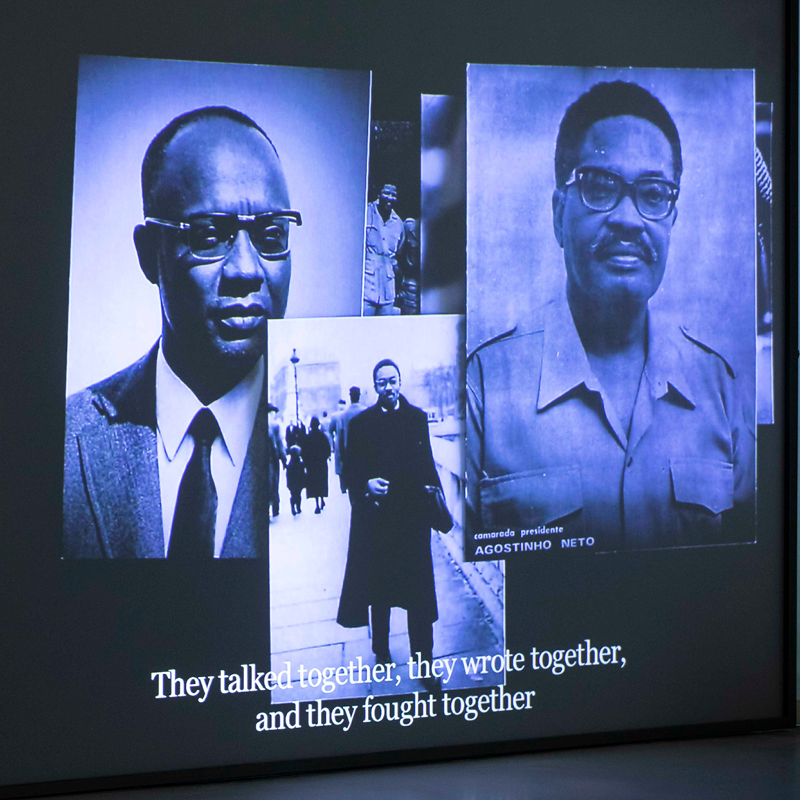

BOUCHRA KHALILI

Foreign Office, 2015

NINA FISCHER & MAROAN EL SANI Freedom of Movement, 2017

KILUANJI KIA HENDA

Le Merchand de Venise, 2010

SARAH WAISWA

Ballet in Kibera (series), 2017

JOHN AKOMFRAH

Peripeteia, 2012

YINKA SHONIBARE

Invisible Man, 2018

ROBIN RHODE

A Day in May, 2013